A Tour of Aldwych Station (closed 1994)

According to my friends and family, it’s difficult to spend time with me without becoming aware of my overwhelming love of the past. It’s true: I love history, I love historical things and much prefer the past to present. Indeed, I have to make a conscious effort to read or watch things that aren’t historical in some way. I thought studying for two History degrees might end up putting me off the subject but quite the contrary – it’s a passion that is here to stay, now a cornerstone of my personality. I sometimes forget, however, that not everyone shares my enthusiasm; there have been many occasions where I’ve found myself regaling someone with an anecdote or two about a ‘pet’ topic but have taken too long to notice the obvious signs of boredom

I’ve since learned to cut back on sharing my various fascinations, especially the more niche ones. Even those friends I studied alongside at University, for example, are unaware that I am utterly captivated by the history of the London Transport system and the development of the Tube in particular. When the chance came up to tour the disused Aldwych Underground Station, I didn’t hesitate to say yes…

According to TfL, there are currently (as of March 2020) 270 stations in use across the London Underground network. But did you know there are over 40 other stations lying dormant under the streets? They are all in different states of both completion and repair: some are partially built, and others fully so. A number look just as they did on the day the last passengers passed through; fascinating time capsules of London’s past. Not all of these ghost stations are accessible: if the above ground station building has been redeveloped or demolished, then it may require a chartered journey from a nearby operational station. In other words, they’re inaccessible to members of the general public. Aldwych is an exception, because it is still occasionally used as a film set and training facility. Nonetheless, access is still tightly controlled and it took me several years of regular hunting and searching to get onto a tour.

To set the scene, here’s some background…

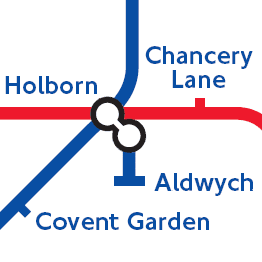

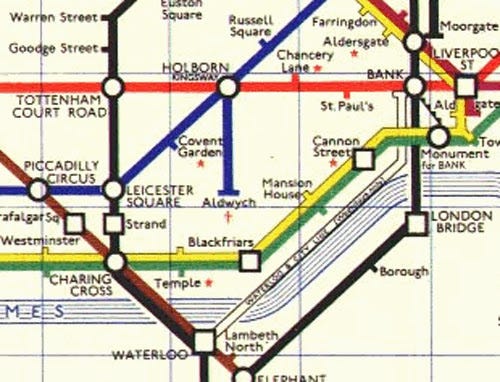

Aldwych station opened in 1907, after two years of construction, intended to ferry theatregoers to and from Holborn. There were two platforms, with eastern and western tunnels. As an effective a shuttle or branch line, passenger numbers were consistently low, with only around 450 a day passing through. This is a crazily low number when you consider that other stations in the early 20th century got upwards of 200,000. Closure was considered on multiple occasions from 1929 onwards. The station was eventually permanently closed in 1994, by which time it was losing LRT (later TfL) £150,000 per year, as the original 1907 lifts that were in operation required replacement. The estimated cost of this work was £3 million, and LRT decided that this was not justifiable. The station closed for the last time on 30th September 1994, which by coincidence, was also my fourth birthday.

The station is situated just off the Strand, close to the Kings College London campus. Temple Station is a two minute walk away. As is the case for many of the older Underground stations, the Aldwych station building consists of the classic terracotta tiled façade designed by the architect Leslie Green. It still bears the name of the line it was originally part of — the Piccadilly Railway, which went onto form the modern Piccadilly line — as well as the original station name of ‘Strand’, which would be renamed as Aldwych in 1914.

Aldwych is unusual in that both its surface buildings and interior have been preserved. In many cases, once a station fell into disuse the land and buildings above ground would be sold off to private individuals, who could use them as they pleased. Many were converted, others demolished then built over. This particular station’s preservation can be accredited to several factors: its history, relatively recent closure and the uses it has been put to in the years since it closed. In 2011, Aldwych Station was granted status as a Grade II listed building meaning that it cannot be demolished, extended, or altered without special permission. It remains the property of TfL. Primarily, this derives from its historical significance.

During the First World War, the eastern tunnel and platform — which was taken out of use in 1914 — were used to house 300 valuable paintings from the National Gallery, protecting them from German bombing raids. The outbreak of the Second World War saw Aldwych come into service again, nightly sheltering hundreds of Londoners from the Blitz. Unknown to those who laid crowded together on the cold concrete of the platform and between deactivated tracks, the Elgin Marbles and other antiquities from the British Museum, were sequestered in the nearby tunnels.

Though its days as an operational station are long gone, Aldwych is still in regular use, most notably as a location for filming. This is not, however, the current main use: it’s most frequent use is as training facility by the Emergency and Security Services. The SAS are known to have trained at Aldwych prior to the London 2012 Olympic Games, as part of their counter-terrorism training. In recent years the London Ambulance and Fire Services have also been training there, to prepare in case the Tube network becomes a target for terrorist attacks again. Aldwych is particularly good for mimicking such attacks, as there are no longer any operational lifts: the only way to and from the platforms is via the narrow 131-step spiral staircase. Crucially, unlike other disused stations, Aldwych does not have trains passing through it, so allows practice scenarios to take place undisturbed.

On entering the ticket office, I’m taken aback by how much of the original interior with the famous green tiles — like the exterior, designed by Leslie Green — remains, although our guide confirms that some restoration work has been carried out. At this point, it looks just like a quiet Tube station and reminds me strongly of Covent Garden without the crowds of aggressive tourists.

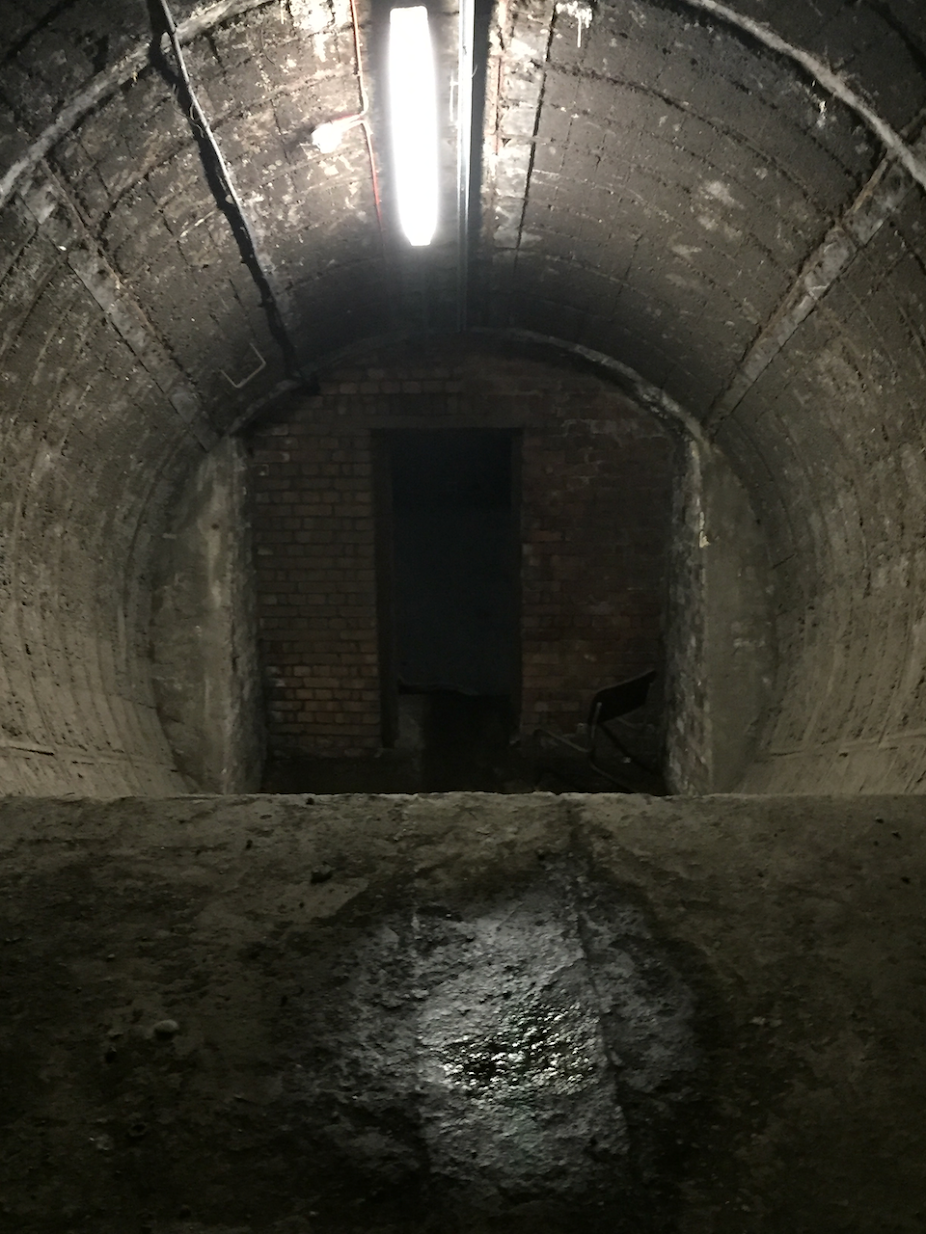

As we move down to platform level, however, things start to become eerie. The state of repair gradually gets worse. It smells dusty and damp. Once we get to the bottom, there is a sudden temperature drop and I become very conscious of my surroundings. It’s not unlike the sensation you get in a derelict building, or on walking home alone through dark and empty streets. There have been paranormal investigations carried out down here in the past (Most Haunted anyone?): I can easily see why someone might think it is haunted.

Both tunnels at Aldwych are still connected to the network so even though the station itself is deserted, the noise of faraway trains echoes down the tunnels. Aside from the voice of the guide, that is all you can hear. The air is very stagnant and fusty, despite wind that blows through from Holborn (the nearest connected and operational station).

According to our guide, at one point in the station’s history it was being considered for expansion so tunnels were built in anticipation of that. Nothing came to fruition, however, but a stretch of unplastered tunnel remains and leads to a dead end.

Largely left untouched since the station was built, there are delicate stalactites forming overhead in this section of tunnel.

This is Platform 2 (connected to the eastern tunnel), which was last used in 1914. The lack of decoration or rendering gives it an unfinished feeling, as if construction was abandoned halfway through. This is misleading: it was used, if only for a brief time, and then stripped back after being taken out of service.

The age of the second platform is apparent from the the lack of suicide pit (i.e. the metre-deep depression under modern Tube station rails that saves many lives annually), the relatively shallow depth of the platform and the crude nature of the rails themselves, which are quite unlike any you will see on the Tube nowadays.

It has a sort of ‘holding bay’ function too: as the line did not extend further, trains had to leave the same way that they came in.

Platform 1 (connected to the western tunnel) is the one that remained in use right up to closure. It is more modern in appearance, with less sense of incompleteness.

It is this platform that is used by production companies for filming, and rails here are operational. There is a disused train – usually stored along in the tunnel but sat at the platform on the day I visited – that be used in filming if needed and moved along the short length of track. The electrical connection to the Piccadilly line is not permanently turned on, however, and is only activated on request.

You may notice the lack of decoration on the platform walls and livery on the train. This is because it is used for filming: each time a crew comes into the station, they decorate as required, then strip everything back and tidy up after they have finished. Recent films to have been shot at Aldwych include Darkest Hour (1917) and a 2014 BBC episode of Sherlock. It is particularly popular as a setting for World War II bomb shelters, because of the lack of modern decoration and amenities, and it features in this capacity in Atonement (2007).

In total I spent about an hour and a half exploring Aldwych, which flew by. The experience was highly memorable, and quite unlike any of my other historical explorations in London.

If you’d like to visit yourself, keep an eye on the London Transport Museum’s Hidden London page, where Aldwych sometimes comes up alongside other tours. Be quick if you spot one, because from experience, places go very quickly and visitor numbers are limited.